Our 2021 Harlow Summer Seminar Series is now available online! You can view them on the WyoScholar Digital Repository.

Our 2021 Harlow Summer Seminar Series is now available online! You can view them on the WyoScholar Digital Repository.

We are searching for a facilities manager to join our team! The facilities manager will oversee day-to-day management of the physical facility, including management of summer staff. For more information and to apply, please visit https://bit.ly/uwnpsfacilitiesmanager

We are looking for two outstanding undergraduates or recent graduates who are passionate about research, nature, and helping things run smoothly. Summer hires will spend June-August at the station, assisting in research activities and helping to make the station run smoothly on a day-to-day basis. For more information and to apply, please visit: https://bit.ly/uwnps22summer

Please share with those who may qualify or be interested. We look forward to hearing from you!

UW-NPS Research Station announces the 2022 Small Grants Program RFP.

Please share with those who might be interested.

The small Grants Program is funded by the National Park Service and the UW-NPS Research Station at the University of Wyoming. It is limited to US academic institutions, government, and NGO researchers conducting their studies in the Greater Yellowstone Area. See uwnps.org/grants for more information, a list of past awards, and a link to annual reports of research going back to 1954.

Grants will be evaluated by a panel of park personnel and faculty in diverse fields based on intellectual merit (will the study advance our understanding in some key way), and relevance to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. We welcome proposals that address Grand Teton National Park research priorities and Yellowstone National Park research priorities, but that is not necessarily a requirement for funding.

We encourage grant submissions by and/or for graduate student research support as these small grants can be a vital source of support for students working in the GYE.

For RFP details and to submit a proposal, go to 2022 UW-NPS Small Grants in InfoReady.

General Contract Schedule

| 1/18/22 | Last day proposals are accepted |

| 2/28/22 | Award notification |

| 5/1/22 | Initiation of contract, start/schedule field work as appropriate |

| 12/1/22 | Progress report due |

| 4/30/23 | Award end date |

Due to the potential risks of the Covid Delta variant, we have made the decision to err on the side of caution and cancel the August 19 Harlow Seminar with Dr. Tarissa Spoonhunter.

If you are interested in Traditional Ecological Knowledge or would like to learn more, please stay tuned for future updates! We still plan to host Dr. Spoonhunter and will make an announcement in the future – keep an eye out for that and for news about the September Harlow Seminars.

The highest diversity of salamanders is found in Southeast United states, but Wyoming is unique to have their only native salamander as their state amphibian, the tiger salamander. These salamanders have several different color variations within the species, subspecies, and region, but typically are dark grey, brown or black with brownish markings (nwf.org).

Tiger salamanders may be seen after heavy rains, but most of the year they are found burrowed underground. They mate during late winter or early spring at breeding ponds and eggs are laid between 24-48 hours after. After eggs hatch, tiger salamanders are able to live up to 14 years in the wild. To learn more about the Tiger Salamander, check out this article for some fast facts and an easy read!

Written by Anna Cressman

PC: Anna Cressman

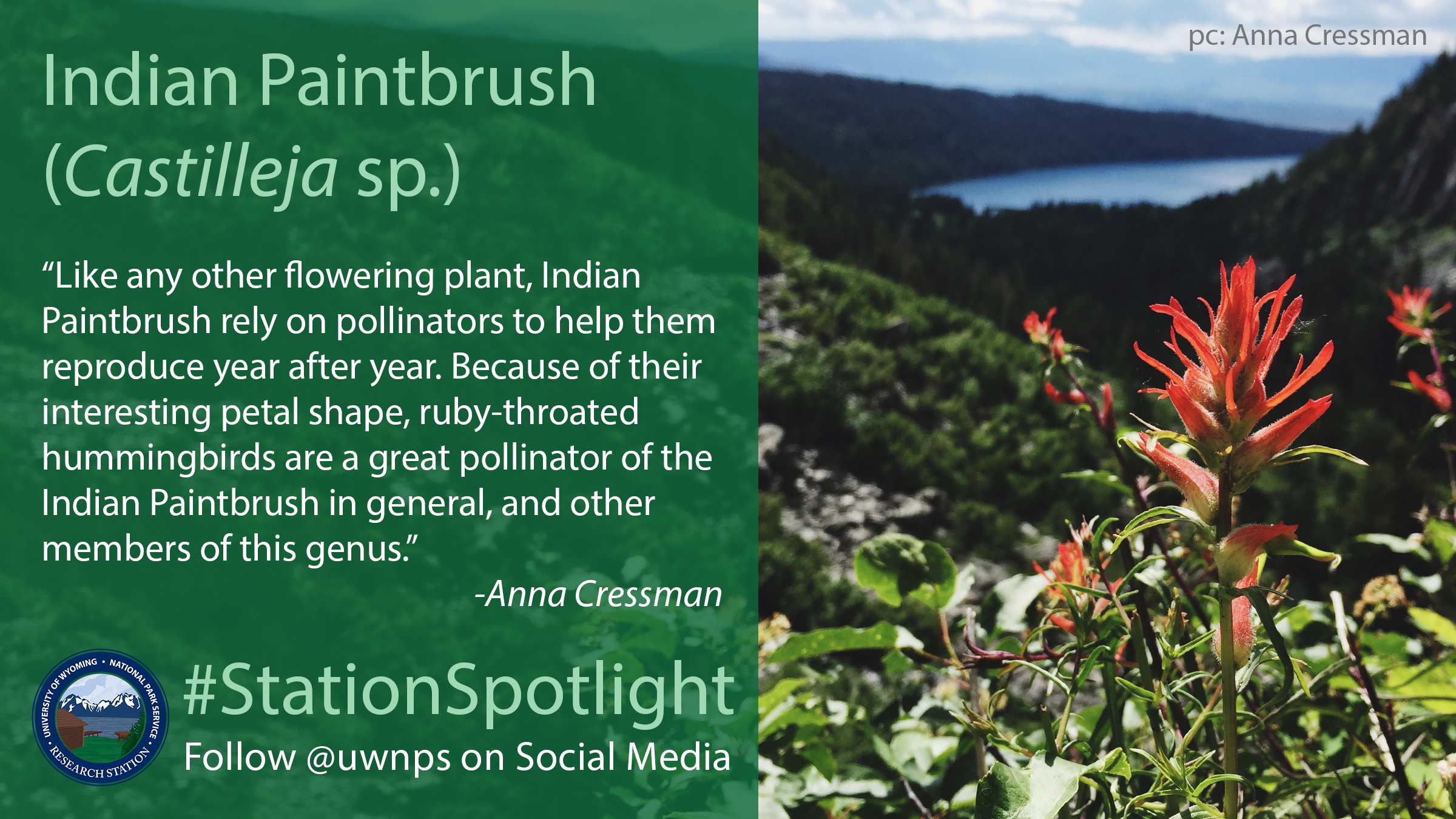

With over 200 species of Castilleja, this species of Indian Paintbrush is native to the United States. Wyoming’s state flower is specifically Castilleja linariaefolia, but we will focus on the species coccinea. Coccinea refers to the red petals that resemble cup-like structures. When we think of plants, we know they photosynthesize and get their energy from the direct sunlight, but these plants are hemiparasites, meaning that they get some of their nutrients from other organisms as well. Most of the time, they will parasitize the perennial grasses that accompany them (USFS), as well as sagebrush.

Like any other flowering plant, Indian Paintbrush rely on pollinators to help them reproduce year after year. Because of their interesting petal shape, ruby-throated hummingbirds are a great pollinator of the Indian Paintbrush in general, and other members of this genus. Since hummingbirds have the long, slim bill to reach the nectar, they are a perfect pollinator for these tubular-type flowers.

Click here to learn about how the Indian Paintbrush got its name.

Written by Anna Cressman

PC: Anna Cressman

Half the size of a grizzly but anecdotally twice as ferocious, these large weasels have a reputation of being some of the meanest animals in the park. Labelled as bad-tempered, solitary, and aggressive, wolverines have been said to fight off bears, mountain lions, and entire packs of wolves; they are even believed to possess evil magic – but does their reputation precede them?

With a surprising amount of strength and endurance packed into their small muscular frame, wolverines are competent predators, but they aren’t cold-hearted killers. Like other animals in the weasel family, wolverines are intelligent masters of survival, able to live in extreme alpine environments. They are adaptable, curious, and opportunistic, travelling 30-40 miles a day through rugged mountain terrain in search of small game, carrion, and plants to eat.

Written by Shawna Wolf

Source: https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=wildlifenews.view_article&articles_id=692

PC: Mathias Appel on Flickr https://flic.kr/p/2ixjhA5

Because of the prominent white stripe running down their back, their stinky reputation, and maybe with a little help from Pepe le Pew, skunks are well-known and easily distinguished critters. They are quite versatile, living in woody and grassy habitats ranging from urban areas to wilderness across the United States.

Skunks aren’t the type to look for trouble, but they are equipped with powerful defense in case trouble finds them. When they feel threatened, skunks raise their tail, arch their back, and stomp their front feet in warning. If the threat presses on, the skunk does not turn away. Instead, they bring their rump around, and we all know what happens next – the skunk releases a powerful, odorous spray that can extend nearly 20 feet away, causing quite the unpleasant experience for the intruder. Alongside its obnoxious stench, the smelly substance can cause pain, nausea, and temporary blindness.

Despite this famous defensive device, skunks unfortunately have an extremely high mortality rate, often being killed by disease, predators, or road incidents within their first year of living. Watch out while driving in the park, especially at night when skunks are most active!

Written by Shawna Wolf

PC: Daniel Arndt on Flickr https://flic.kr/p/GeTxnA

The northern flying squirrel is a small rodent most commonly found in conifer dominated forests from the treeline in northern Alaska and Canada and down into the middle of the continent in Michigan, Wisconsin, California and Colorado. They can be found in deciduous and mixed forests throughout their range, and while they are not frequently seen or overly abundant, they have been found in the Jackson Hole area and Grand Teton National Park. These silvery grey squirrels inhabit treetops and, as the name suggests, they can “fly” from tree to tree to get around the forest. They do this with a furred patagium which extends from their wrist on the forelimbs to the ankles in the hind limbs. This is very advantageous to them as they are quite clumsy on the ground, so being able to glide from tree to tree and fill up on nuts, acorns, and lichen protects them from becoming an easy meal.

Even if you do happen to be in an area populated with flying squirrels, don’t expect an easy viewing opportunity. As evidenced by their large black eyes, Northern flying squirrels tend to be more active at night making them pretty tough to spot in the canopy for the casual wildlife viewer. Learn more about these rambunctious rodents.

Written by Timothy Uttenhove

PC: Daniel Arndt on Flickr https://flic.kr/p/mtGtPQ